Does HPW create value for farmers through the block farms and is the block farm model sustainable for the company without external support?

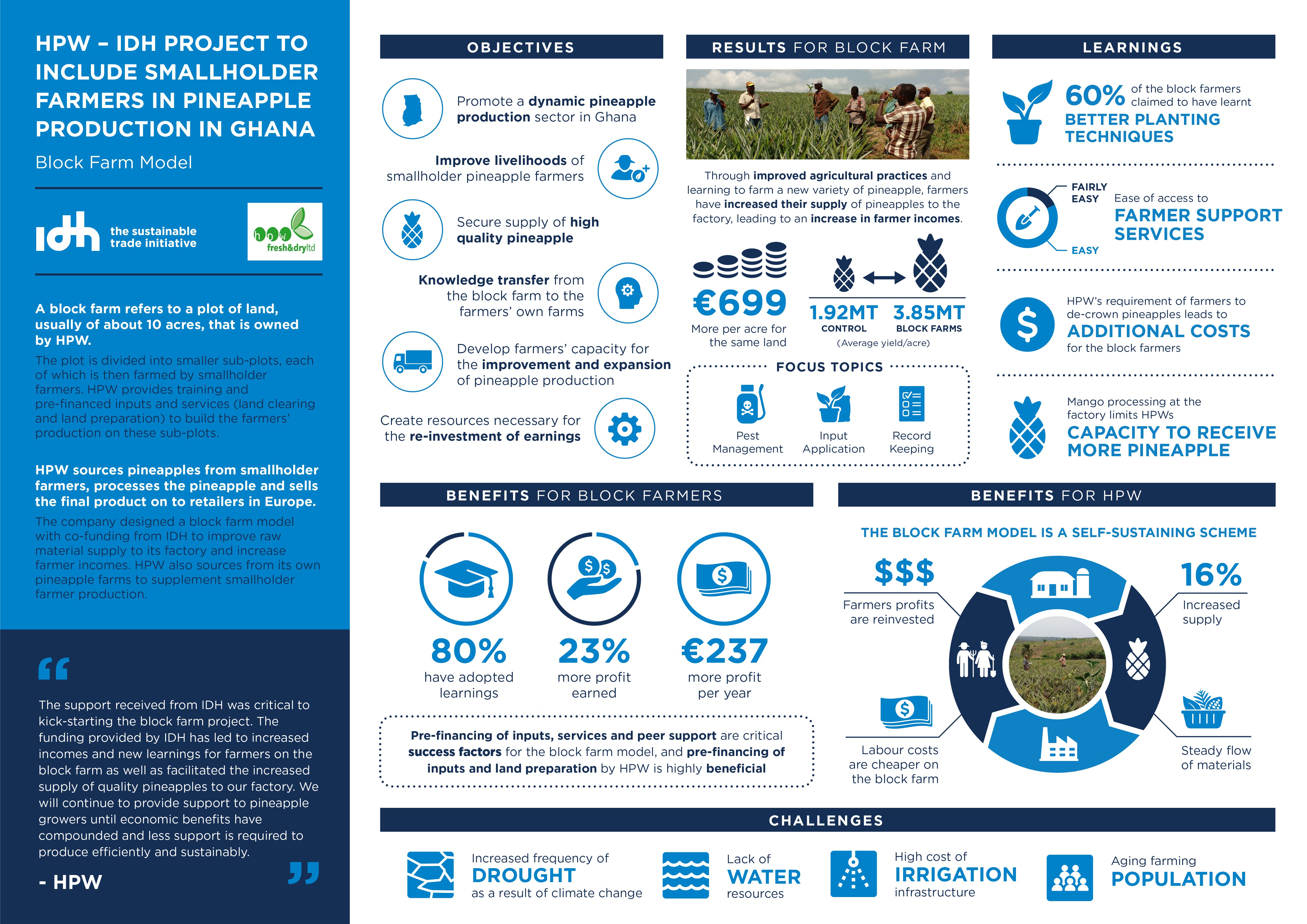

The block farm model creates economic value for the farmers, and for the company as well, as it ensures a steady flow of raw materials to the factory. On average, the block farm yields €484 more in profit for farmers on the block farm project than HPW’s farm and €237 more for block farmers than the farmers in the control group for the same production.

Farmers value their relationship with HPW, they credit their knowledge gain on new production methods to HPW’s training and financial support. They also credit technical supports a reason for a higher yield than they are used. Block farmers only appear to be disgruntled in the aspects of transparency on price fixing, and de-crowning of pineapples at harvest.

The block farm model is a self-sustaining scheme, profits from farmers can be reinvested into subsequent pineapple production cycle, and the harvest serves as supply to the factory. Also, mother plots have been established for the procurement of high-quality suckers and consequently, a reduced cost of production on subsequent production rounds.

It is evident that most farmers would not have mastered pineapple production without HPW’s support, however, ensuring continuity of sustainable production will involve further optimization of the learning and support process. This is because it is easier for farmers to comply with the right protocols when inputs and technical support are readily available. The gains and impact of the block farm model can be further sustained via the company’s existing initiative for pineapple producers.

Overall, farmers view HPW’s training as being effective and beneficial. 55% of the company’s interaction with farmers is during training, 45% of the encounter is farm visits. 92% of block farmers interviewed affirmed that the practices learned during the training sessions were beneficial to them. 88% rated the training as being of high impact and stated that although block farmers have been producing pineapples for an average 14.9 years, most were not familiar with standard production methods taught by HPW training.

About 89% of block farmers identified fertilizer and pesticide application protocols as a new technique learned during the training on the block farm.

A farmer recalled, ‘We didn’t know we had to apply fertilizers more than once after planting, but they (HPW) taught us the right things, and the difference is evident.’ 60% also claimed they had learned better planting techniques such as plant spacing, use of plastic mulch, as well as improved methods for record keeping. 16% cited weeding methods. On the ease of farmers’ access to these services, 88% find it easy; 12% ‘fairly easy.’

Most of the block farmers interviewed (80%) claimed to have implemented the learnings also on their farm. Of those who declared to have implemented the new techniques learned in the block farm on their private farms, 88% asserted to have experienced benefits. Productivity is said to have been increased by an average 31.6% based on knowledge acquired on the block farm. This was credited to lower incidence of pest, bigger fruits, shorter production cycles, uniform growth on fields, and lower post-harvest losses. The most significant impact reported was knowledge of production methods for a new variety (100% of block farmers agreed to this). While the HPW factory accepts both Smooth Cayenne and MD2 pineapple varieties, farmers consider the training and support provided for the MD2 variety as more beneficial since it’s bought by HPW at a higher price.

However, some of the block farmers admitted that they did not implement learnings on their private farms accrediting this to the lack of funds, which hinders them from procuring inputs promptly. According to these farmers, being part of a block farm is the primary advantage since they are not only trained but also empowered to implement practices immediately with the right inputs.

In 2015, HPW was unable to meet buyers’ demand due to a low supply of raw material (pineapples). This situation influenced the decision to establish a more systematic approach of interaction with the smallholder farmers to enhance the supply of high-quality raw materials to the factory. From this perspective, the block farms would be considered beneficial to the company if it ensures a steady flow of raw materials to the factory. In the first round, the block farmers produced about 150MT of pineapples more than projected. Generally, the number of pineapples supplied to the factory increased by 29%.